Introduction: Geopolitics Meets the Technological Age

The global balance of power is undergoing a seismic shift driven by the convergence of geopolitical rivalry and technological revolution. The post-Cold War era of globalization and economic integration is giving way to a new multipolar order defined by regional blocs and strategic competition. At the heart of this transformation lies a race for technological supremacy that could reshape the global hierarchy more fundamentally than traditional measures of power.

As automation and artificial intelligence advance, the gap between technological leaders and followers threatens to become permanent. Nations that fail to secure their position in this new order risk irreversible decline, making innovation capacity and talent attraction critical to national power. For smaller and mid-sized nations, this presents an existential challenge: they must navigate between emerging power blocs while building technological capabilities, all without the luxury of the resources that superpowers enjoy.

South Korea exemplifies this dilemma. Despite its economic achievements, Seoul's recent foreign policy choices, particularly toward China, reflect a dangerous overestimation of its strategic position. Its approach appears increasingly disconnected from both global power dynamics and technological imperatives. Without a course correction, South Korea risks compromising not only its security but its future prosperity in an age where technological capability increasingly determines national fate.

1. The Two-Headed Dragon: Geopolitics & Technology

The 21st century is being shaped by an unprecedented convergence of traditional geopolitical power and technological dominance. Nations are coalescing around influential "hubs" – with the United States anchoring the West and China emerging as Asia's gravitational center. This realignment goes beyond conventional alliance-building; it's a strategic restructuring of global supply chains, resource networks, and technological ecosystems.

What makes this era distinct is the looming technological threshold that threatens to permanently divide nations into those who possess the core technology and those who do not. As artificial intelligence and robotics advance toward autonomous innovation and production, the gap between technological leaders and followers could become unbridgeable. This isn't merely about economic advantage – it's about the fundamental capacity to compete in a world where AI-driven automation determines everything from military capability to social development.

The U.S.-China technological rivaly illustrates this new paradigm. China's AI strategy aims for global leadership by 2030, leveraging data advantages from its vast population. The U.S. counters by capitalizing on its fundamental research strengths and private sector innovation. Both powers are restructuring global supply chains through initiatives like the CHIPS Act and massive domestic investments in semiconductor manufacturing. This competition is forcing traditional allies to choose sides – as evidenced by Japan and the Netherlands aligning with U.S. semiconductor export restrictions despite economic costs.

For nations without leading positions in these technologies, the challenge is existential. Countries that once relied on manufacturing or resource extraction must now navigate a world where technological capability increasingly determines economic viability. The ability to participate in advanced technology ecosystems has become as crucial as traditional military or economic strength.

This new reality presents a stark challenge to traditional assumptions about national power. While democratic values and political systems remain important for civil society, they offer little protection against technological obsolescence. A nation's future position in the global hierarchy will increasingly depend on its ability to either develop or rapidly adopt next-generation technologies, particularly in AI and robotics.

This is the cold reality of our transition period: nations must excel in both technology and geopolitics to survive. Until technology matures enough to emerge as the sole dominant force shaping the world in the coming decades, every nation, company, and individual must navigate this two-headed dragon. Those who fail to secure their position now risk being left behind in a post-reset civilization where technological capability alone determines power.

2. South Korea’s Missteps

The growing anti-China sentiment in South Korea exemplifies a dangerous disconnect between perception and geopolitical reality. Recent conspiracy theories about Chinese territorial ambitions toward the Korean peninsula ignore fundamental strategic logic: annexing a neighboring country with a different language and culture carries enormous costs, especially when that territory lacks crucial resources. For China, such an action would be an economic and political burden rather than a strategic gain.

Yet South Korea's recent policy decisions suggest a misreading of its strategic position. The banning of Chinese technology platforms like Deepseek mirrors the protectionist measures of superpowers – nations that possess the geopolitical leverage and technological base to weather economic retaliation. As a mid-sized nation heavily dependent on international trade, South Korea cannot afford such unilateral actions without risking significant diplomatic and economic consequences.

This overconfidence stems partly from South Korea's faith in its U.S. alliance and democratic credentials. While these are valuable assets, they neither guarantee security nor ensure technological superiority. In today's world, true power derives from either technological leadership or substantial geopolitical leverage – the former through a powerful ecosystem of tech companies and the latter through vast resources, influential financial systems, or large domestic markets. The United States and China can afford protectionist policies because they possess these advantages. South Korea, despite its impressive economic achievements, lacks this degree of autonomy.

The reality is stark: without the vast domestic market of China or the technological ecosystem of the United States, South Korea's unilateral attempts to distance itself from major powers risk self-inflicted damage. Its current trajectory suggests a dangerous overestimation of its strategic position – one that could undermine both its security and its technological future.

3. Lessons from History: Why Trade Bans Often Backfire

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my friend, Dongsung Shin, for generously sharing his extensive knowledge of China, geopolitics, and world history. The historical examples presented in this section are inspired by his insightful writings.

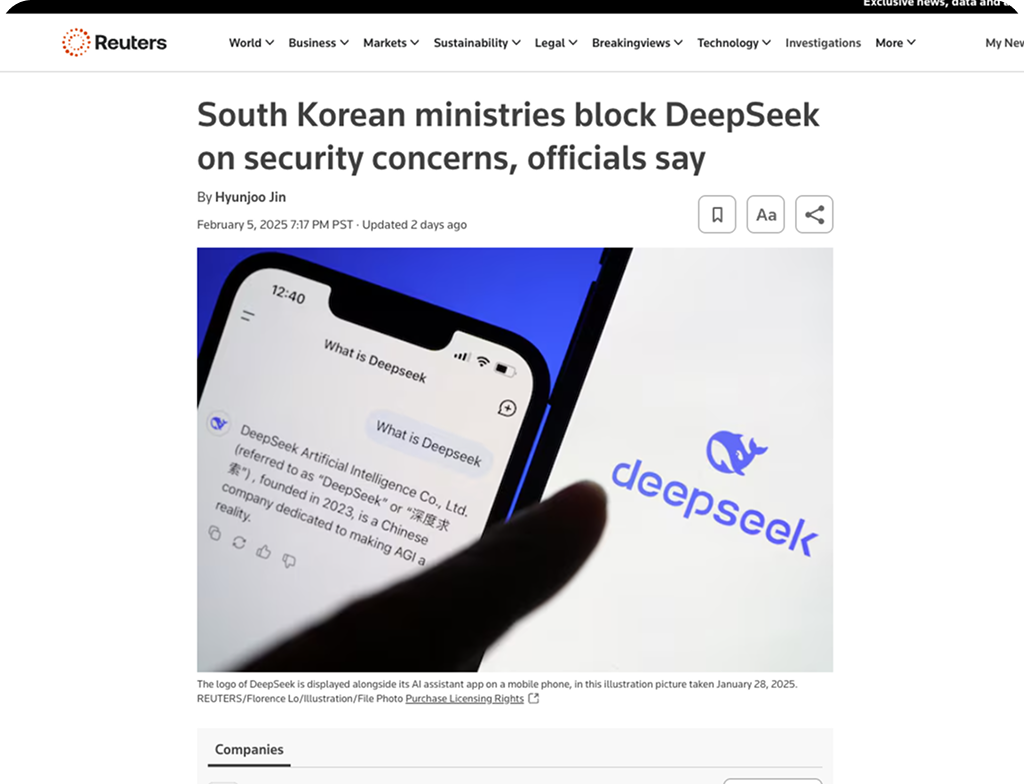

History offers compelling evidence that short-sighted trade restrictions often harm their initiators more than their targets. Two pivotal European cases illustrate how such measures can inadvertently strengthen the intended target while damaging the initiator's economy.

Napoleon's Continental System proved to be a strategic blunder. By attempting to isolate Britain through a European trade embargo in the early 1800s, France inadvertently catalyzed British maritime expansion. The embargo, aimed at starving Britain of vital markets, backfired and spurred the British to develop robust overseas supply chains through colonial expansion. Meanwhile, French territories suffered from severe inflation and domestic shortages as the embargo disrupted established trade patterns across the continent.

Britain’s World War I embargo against Germany yielded similarly counterproductive results. Rather than crippling German industry, the blockade accelerated German self-sufficiency. Germany developed alternative supply chains through Denmark, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, ultimately emerging with enhanced industrial capabilities and reduced dependence on British technology.

These historical lessons hold particular relevance for South Korea today. As a mid-sized economy lacking the vast resource base or domestic market of a superpower, South Korea faces even greater risks from restrictive trade policies. Banning Chinese technology without possessing a robust domestic alternative could weaken South Korea's economic position while encouraging China to develop independent alternatives.

The pattern is clear: attempting to isolate more resourceful powers typically rebounds against the initiator, creating new trade networks that ultimately strengthen the targeted nation. For South Korea, pursuing such policies risks undermining its own economic security.

4. A Middle-Ground Strategy: Five Key Pillars

For mid-sized nations with strategic geography, neutrality and openness can become powerful assets. Singapore and Switzerland demonstrate how maintaining balanced relationships and fostering business-friendly environments enable countries to thrive without alienating global powers. South Korea could leverage this approach to become a diplomatic and economic bridge between the United States and China. Achieving this vision requires strengthening five fundamental pillars: robust institutions, cultural openness, technological innovation, business dynamism, and balanced diplomacy.

4.1. A Trustworthy Financial and Legal System

International investors and technology firms require consistent rule of law, reliable contract enforcement, and secure banking systems. Without these fundamentals, South Korea will remain a challenging market to engage with. Recent events — such as the martial law declaration of December 2024 — have further undermined investor confidence and raised questions about political stability. Moreover, the country's reliance on domestic cybersecurity vendors has exposed systemic vulnerabilities in its banking and information services sector.

Robust and trustworthy institutions are the backbone of a strong currency and international presence. Strengthening these foundational institutions is essential not only for building credible international partnerships but also for fostering a sustainable business ecosystem that can generate technological breakthroughs critical for their survival in the coming decade of global transformation. Continuing to ignore these institutional weaknesses threatens South Korea's long-term viability as a competitive nation.

4.2. Cultural Openness

In an era of global talent mobility, cultural openness has become a critical factor in national competitiveness. Singapore's success as an innovation hub stems largely from its embrace of foreign expertise. By contrast, South Korea's cultural landscape presents significant barriers to attracting global talent.

The challenges run deep. South Korea's rigid corporate hierarchies, insular worldview, and cultural resistance to external criticism create an environment that talented professionals actively avoid. When given the choice between Singapore and South Korea, global innovators consistently choose the former — not just for its economic opportunities, but for its cosmopolitan atmosphere, institutional reliability, and openness to diverse perspectives.

This cultural insularity stems partly from a gross overestimation of South Korea's geopolitical standing, fostering a form of cultural arrogance that hinders meaningful international collaboration. The nation's difficulty in accepting constructive criticism further compounds this problem, creating an environment where innovation is stifled by conformity and resistance to change.

While cultural transformation is undoubtedly challenging, it's not optional. Culture forms the foundation of innovation, and without becoming a true innovation hub, South Korea risks irrelevance in the rapidly evolving global order. The stakes are existential: the next decade will determine whether South Korea can transform itself into Asia's innovation center and a meaningful middle ground between world powers, or fade into historical obscurity.

This cultural shift requires fundamental reforms across corporate hierarchies, social institutions, and immigration policies. The goal isn't to abandon Korean cultural identity, but to evolve it into one that can thrive in an interconnected world where innovation drives national success.

4.3. Accelerating Technological Development

South Korea faces a critical challenge in technological development. While protecting domestic companies might seem politically expedient, this approach fundamentally misunderstands the nature of technological innovation. Unlike the United States or China, South Korea lacks the market size and resource depth to nurture innovation through protectionism alone.

Until AI reaches the capability to automate technological breakthroughs, innovation will continue to depend on human pioneers. The gap between world-class talent and second-tier expertise remains vast, particularly in cutting-edge fields. While AI has made product development more accessible, South Korea's absence from core AI technology development puts it at a severe disadvantage. This technological dependency will rapidly erode South Korea's strategic leverage in the coming years.

The path forward requires a two-pronged strategy. First, South Korea must invest aggressively in core technological breakthroughs, particularly in AI and robotics. While this presents an uphill battle against U.S. and Chinese advancement, the alternative — developing deep foreign dependencies in these foundational technologies — threatens the nation's economic backbone across all sectors.

Second, South Korea must embrace foreign technologies in the interim. The current performance gap between domestic and international technology firms demands increased competition, not protectionism. Banning Chinese technologies while remaining dependent on U.S. alternatives creates dangerous asymmetric dependencies.

Without addressing these technological imperatives, South Korea risks falling into permanent technological subordination. The nation must balance immediate technological access with long-term technological independence — a delicate equilibrium that requires both openness to foreign innovation and committed investment in domestic capabilities.

4.4. Creating a Dynamic Business Ecosystem

Advanced technology cannot thrive in isolation. It requires an integrated network of distribution channels, logistics solutions, venture capital, and supportive regulations. With the Indian Ocean region increasing its stake in global trade volume while the US maintains its economic strength, South Korea's strategic location remains a valuable asset that must be leveraged before this geographical advantage diminishes.

By enhancing corporate governance, improving regulatory transparency, and building close ties with businesses across both US and Chinese spheres of influence, South Korea could position itself as an attractive base for international firms. Channel partners and logistics companies would benefit from establishing regional outposts in South Korea if provided with the right business environment. Technology companies could leverage South Korea's ecosystem to build products locally while accessing diverse regional markets, reinforcing the country's role as a strategic middle ground.

This transformation requires dismantling decades-old protectionist practices that have sheltered their domestic companies from global competition. The government must force them to compete on quality and innovation rather than allowing them to monopolize the local economy at consumers' expense. The pursuit of isolated national standards born from fear of foreign competition must end.

Most critically, South Korea needs to embrace international standards rather than insisting on developing proprietary ones. Creating unique national standards is a privilege reserved for entities with substantial technological and geopolitical leverage — neither of which belongs to South Korea. Clinging to isolationist "Korean ways" while the world moves forward without them reflects a dangerous misreading of their national power, and could have severe long-term consequences if not addressed promptly.

4.5 Maintaining Balanced Regional Relationships

In a part of the world where alliances often hinge on immediate national interests, antagonizing a major neighbor can quickly lead to economic and diplomatic setbacks. The rise of anti-China sentiment in South Korea risks long-term damage to trade ties and regional stability, especially given the country’s limited geopolitical heft. A more balanced approach would center on constructive engagement with both the United States and China, carving out a niche that capitalizes on the strengths of both superpowers rather than becoming a casualty of their rivalry.

Taken together, these five pillars forge a renewed model of statecraft that values technological innovation, openness, competitive excellence, and strategic diplomacy over false confidence in geopolitical importance or self-defeating economic policies. Through successful implementation of these foundational reforms, South Korea can pivot away from its current trajectory toward the stability, influence, and prosperity that a genuine middle-ground strategy promises.

Conclusion: Embracing Reality for Future Prosperity

South Korea stands at a critical juncture as the global balance of power shifts toward a new reality driven by the convergence of geopolitics and technological revolution. The emerging era of AI and robotics poses an existential challenge to its national relevance. As automation technologies mature in the next 3-5 years and artificial general intelligence looms on the horizon, the divide between technological "haves" and "have-nots" could become virtually permanent.

For nations lacking vast resources or domestic markets, the choice is stark: adapt strategically or fade into irrelevance. Historical lessons, from Napoleon's Continental System to Britain's WWI embargo, demonstrate how isolationist policies implemented without careful deliberations often backfire on their initiators. South Korea's recent moves toward technological protectionism echo these ill-fated strategies.

The path forward lies in a middle-power approach built on five crucial pillars: robust institutions, cultural openness, technological innovation, business dynamism, and balanced diplomacy. When properly implemented, these foundations will position South Korea as a bridge between competing spheres of influence while developing the technological capabilities essential for survival in an AI-driven future.

Success demands clear recognition of both opportunities and limitations. Neither alliances nor democratic values alone can guarantee prosperity in a world increasingly shaped by technological capability. South Korea must leverage its strategic location, educated workforce, and industrial base through policies that embrace openness rather than isolation. Only then can it pivot from its current trajectory into a true middle power, securing its place in the emerging technological order.